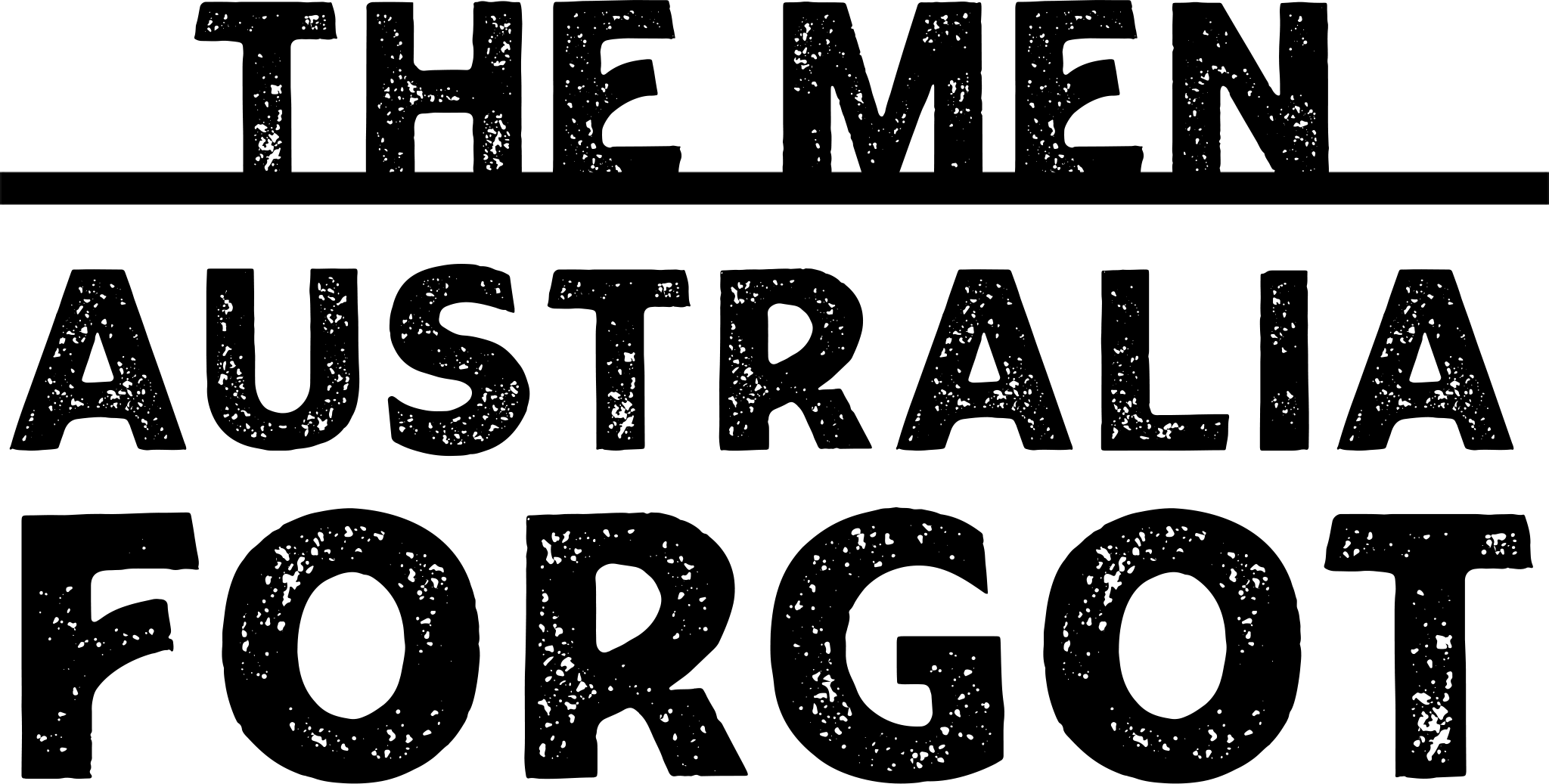

10 NOVEMBER 2024 – Exactly 60 years ago today, Prime Minister Robert Menzies announced the return of conscription to bolster Australia’s army amid major geopolitical turmoil.

He projected understanding of the “difficult personal, social, economic, and perhaps political problems” the decision would create.

But it was the brutal quip of Labor’s Clyde Cameron that best captured some of the angst at the time, and why many Nashos today are frustrated with how their lives were dictated.

As Mr Menzies explained the need for volunteers to continue stepping forward even with conscription — “we would wish the volunteer spirit, which has meant so much to Australia in the past, to continue,” as revealed in Hansard records — Mr Cameron interjected with a scathing personal attack on Menzies’ past, and the famous situation in 1916 when his family exempted him from service:

[MENZIES] Both the Government and the nation would urge that as high a percentage as possible of those in our armed services should be those who, of their own choice, and in the spirit of a great national tradition, have joined one or other of those Services.

Mr Clyde Cameron:

– I know one who dodged it in 1914.

Sir ROBERT MENZIES:

– You do not. You must not repeat other people’s lies.

Mr Clyde Cameron:

– Well, 1915.

Sir ROBERT MENZIES:

– That is a very bad habit, Clyde, and I advise you against it. Indeed, so far as the Regular Army is concerned, volunteers will continue to be of fundamental importance to the effectiveness of the force.

The moral of the story was about choice and the erosion of that fundamental right by a man who benefited from it years before.

Was it ethical that Menzies could suddenly force 7 per cent of the 20-year-old male population to serve when his family had the choice to exempt him from enlistment for the Great War 48 years beforehand?

Two of Menzies’ older brothers had already committed to serve, so his parents wanted to protect one of their sons, but as the Robert Menzies Institute highlights: “No such exemption on family grounds would be included in this new legislation, which would compel young Australians to risk their lives against their own will.”

Various politicians accused Menzies of hypocrisy over this perceived double standard throughout his career. However, it is futile holding him to this in the context of a national security crisis, when conflicts loomed on three fronts and without the manpower to cope.

Instead, and more importantly, Mr Cameron’s remarks allude to the sensitivities of conscription: the lack of choice people had, how unforgiving it was, and the many conflicting factors in overriding human rights for the sake of national security.

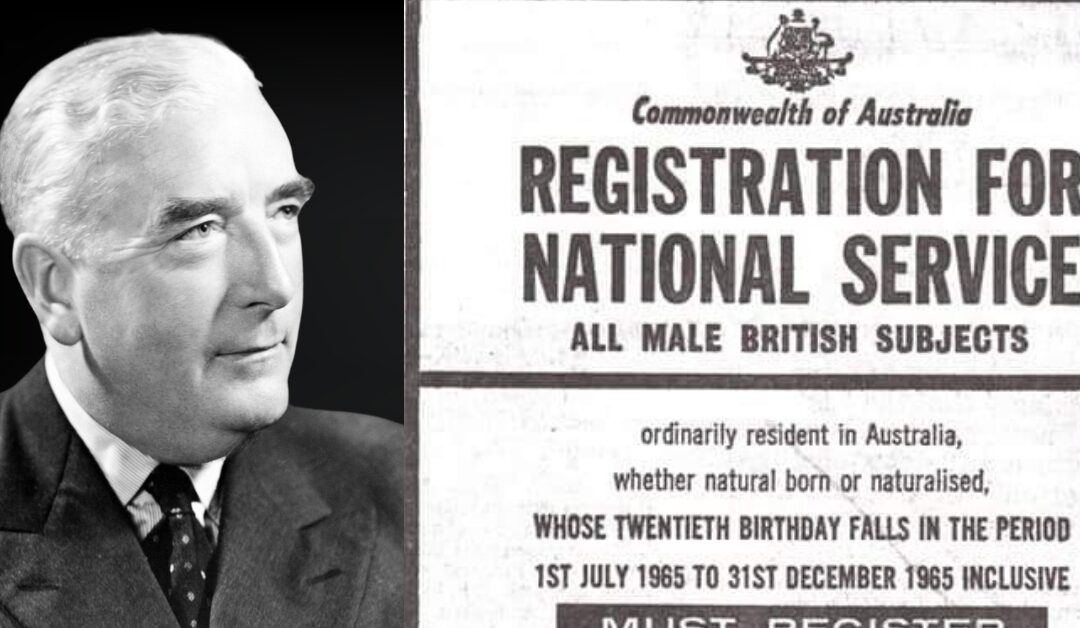

The National Service Scheme of 1964 to 1972 was ruthless. Never before had men been conscripted to join the regular army during peacetime (the Vietnam conflict was never declared a war).

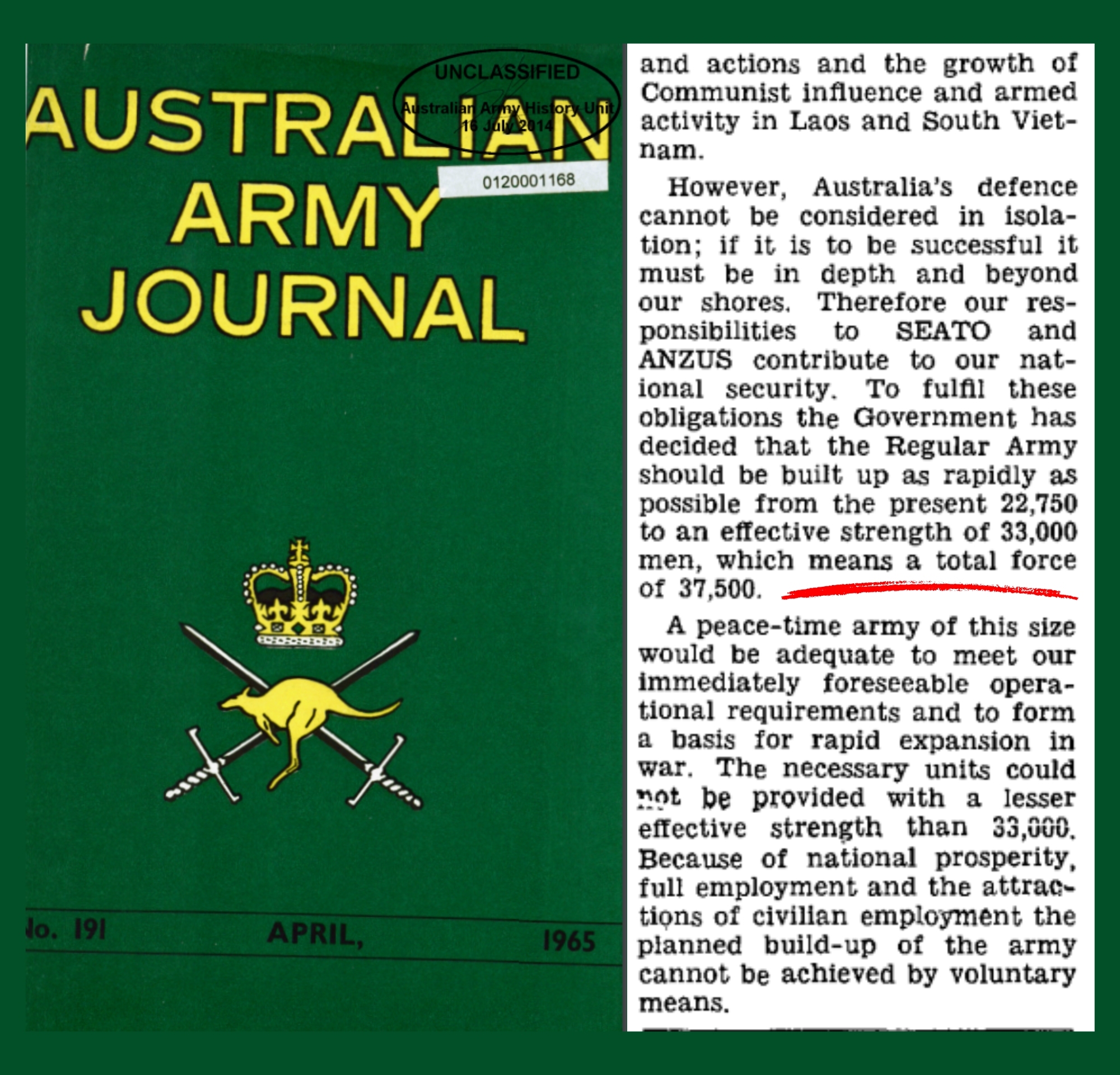

In 1965, the regular army only had 22,750 personnel – well short of the minimum of 33,000 soldiers required to handle operational requirements. Nashos were rushed in to fill the void, making up just shy of a third of regular troops, a huge chunk by any standard.

During the 6-year conscription scheme, more than 63,000 Nashos were enlisted for a total of two years at first, which was later reduced to 18 months. Approximately 16,000 served overseas. While the majority went to Vietnam, the others joined regular troops in places like Malaya and Borneo on peacetime operations that occasionally turned hostile in confrontations against communist forces. The lack of war declarations in those regions had a crushing effect later in life when the government ruled battle-wearing Nashos ineligible for the Gold Card because they were regarded as having not served in a war zone.

Regardless of the deployment location, conscription created a host of other crippling consequences that go unnoticed today. For example, Nashos suffered pay cuts when they sacrificed their jobs to serve. Some lost their entire careers, unable to pick up from where they left things before enlistment. All this without adequate reparation, fueling acrimony among many of them today.

On this day, November 10, 2024, we stop to reflect on what they endured – 60 years on from when their freedoms were jeorpardised.