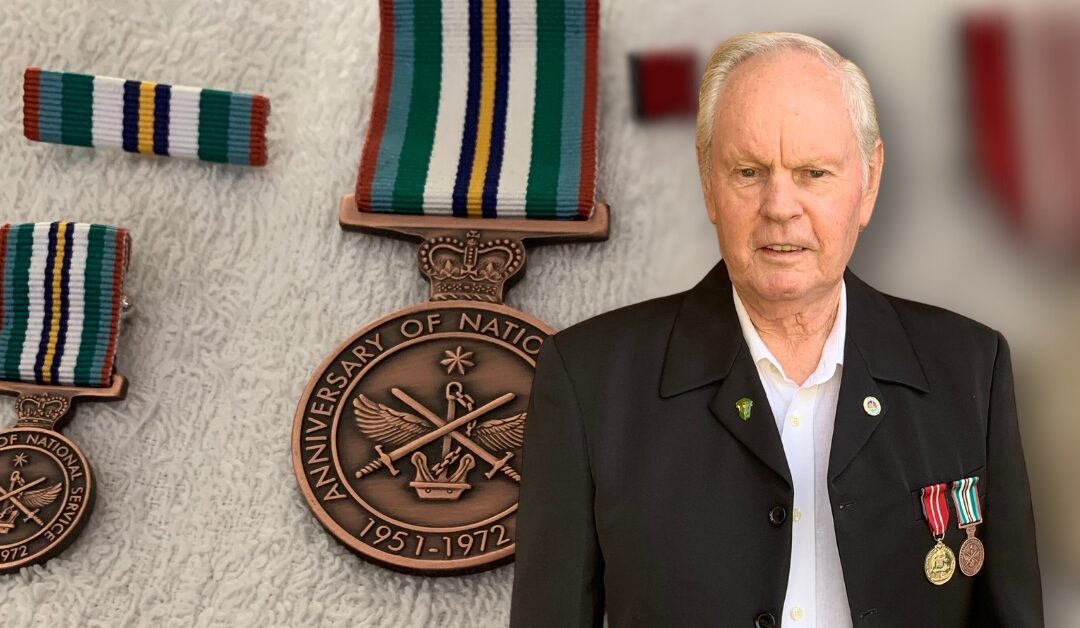

Gold Coast-based Nasho John Smith proudly displays his medals after receiving them last year.

Nashos had to wait 30 years for a basic medal acknowledging their service. Here is the untold backstory of what led to it and insights from those who made it happen, including from the minister in charge at the time.

Few things in life make John Smith’s heart melt as much as seeing his 3-year-old granddaughter wearing his service medals.

“There she was in her pyjamas, running around with a big smile on her face holding up my medals up over her heart, saying ‘Elsy loves Poppa’s army medals,’” he said.

“It was so cute, really great to see, but other than that, yeah, very happy with them, absolutely.”

Mr Smith was conscripted to the infantry in September 1966, where he spent the next two years primarily as a signals operator with 5 RAR, based in Australia.

He counts himself as one of the lucky ones who had a positive experience in the army and easily reintegrated into civilian life.

“After working in retail all my life, it was an eye opener, and it was great to see the camaraderie, so I enjoyed it,” he said.

Having something to show for his two years of service that he could pass onto his grandchildren was a major missing piece in his life until recently.

The revelation came last year when he joined Nasho Fair Go, which is on a mission to find and help as many Nashos as possible.

Through them, he discovered he was entitled to the White Card and two medals — the Anniversary of National Service Medal 1951-1972 and the Australian Defence Medal.

Both medals arrived in time for him to wear them on Anzac Day this year.

“Very proud, mate, very proud,” he said.

“It was worth waiting for, I can assure you of that.”

John’s granddaughter Elsy dances around the living room with his medals.

Mr Smith claims that nobody from the government notified him about the entitlements available to Nashos at any point in the last 58 years since leaving the army.

This is a common thread connecting the stories of the 1964-72 Nashos — the majority of whom were not formally recognised for their service until decades after the last man was discharged in 1974.

While the 15,000-odd Nashos who went to Vietnam were given an official welcome home parade in 1987, nothing was done for the more than 67,000 Nashos who served elsewhere in Australia, Borneo, Malaysia and Papua New Guinea.

The anniversary medal was the first major step to fix this when it was launched in 2001.

Nasho Fair Go President Geoff Parkes said it is inconceivable today that a group of veterans would wait 30 years to receive a basic acknowledgment of service.

“It got to the stage where most of us thought we were never going to be thought of again, that it had passed us by, that we were totally forgotten,” he said.

“We just went on with our lives. At that stage I didn’t even think about it, I was just working away, and it was a total surprise when it came in the mail.”

While appreciative of the gesture, Mr Parkes said progress towards reparation has stagnated since the medal was introduced and fears that politicians have overlooked the need to do anything else.

“We can’t take it [our medals] to the hospital to get a new knee if we need one, so we’d much rather some material health benefits than the medal,” he said.

But what led to the creation of the National Servicemen’s medal, and why did it take so long for the government to act?

The Men Australia Forgot has the untold backstory and exclusive insights from those who made it happen.

John Smith then and now – as a 21-year-old conscript (left) and now, aged 78 (right).

“Minister, we should talk, let’s make this happen”

By the late 1990s, many Nashos were incensed by the ambivalence and disinterest surrounding their cause, prompting a small group of them to campaign for better recognition.

It started with the late Barry Vickery, a Vietnam veteran and Nasho who founded the National Servicemen’s Association of Australia in 1987.

Mr Vickery passed away in 1991, so he never got to see the result of his efforts, but he made an extraordinary contribution to the push for medallic recognition.

Eventually the association found an ally in former federal minister and member for Moreton Gary Hardgrave.

“As a local member, I was able to go to the Brisbane south National Servicemen’s Association,” Mr Hardgrave said.

“They put to me the fact that there was this medal that they believed should have been struck for the Nashos, the ones who were in that 51 to 72 intake.

“The point they made was awfully compelling, awfully compelling, and I took the case to the veterans’ minister who was Bruce Scott, and Bruce Scott said he agreed and to make it happen.”

While Mr Scott used his powers to legislate the medal, Mr Hardgrave brought it to the attention of the Coalition in a closed door meeting between the Liberals and Nationals.

“I represented them in the party room, and I used the line, I said, ‘they’ll always remember if you give it to them, but they’ll never forgive you if they don’t,’” Mr Hardgrave said.

“By the end of the debate, with a couple other colleagues joining in and offering similar points of view, the Prime Minister pointed to Bruce Scott as the veterans’ minister and said ‘minister, we should talk, let’s make this happen.’”

Mr Hardgrave, whose father served in the CMF as a Nasho, said they were treated poorly.

“I think they were seen as the ones that were reluctant to participate in the war, which is really unfair – they were conscripted,” he said.

On 26 April 2001, former Prime Minister John Howard announced the Anniversary of National Service Medal for Nashos who served between 1951 and 1972.

The medal was officially established in October that year.

Bursting with pride

Former veterans’ affairs minister Bruce Scott said legislating the medal was “right at the top” of his most satisfying moments as a politician.

“That will forever be for me one of those moments, where — as ministers you don’t always get happy days — I felt a sense of satisfaction,” he said.

“But they came forward with their submission, they came forward with their request, and I said, yes, it’s never too late to correct something that should have been put in place way back.”

Mr Scott felt strongly that after the way Nashos were treated it was crucial to set a new tone and quash any doubt that they were unworthy of recognition.

Former veterans’ affairs minister Bruce Scott, the leader responsible for legislating the Anniversary of National Service Medal 1951-1972.

“John Howard was always saying to me: ‘Bruce, whatever we do, we must always err on the side of being generous and recognising service, rather than try to find a reason why we wouldn’t do it,’” he said.

He said it was incredibly special seeing the medals on display for the first time.

“I’ll never forget, they had a Nasho march in Sydney, and I was standing along with the senior military people,” Mr Scott said.

“They took the salute when they marched past the Sydney town hall, and they felt so proud, as they should.

“It was absolutely right — too long to get there.”

There are two key reasons why it took so long to recognise the Nashos. The National Archives of Australia stated that society was so opposed to the Vietnam War era that there was no appetite to support or honour veterans after the conflict, which bred a long term apathy among government ranks towards helping them.

According to the archives, it took until the late 1980s – some 20 years after the conflict – for the public to support commemoration and recognition of the Vietnam veterans. The Nashos who served elsewhere during that time were largely ignored until the National Servicemen’s Association started speaking out.

Reflecting on what it took to legislate the medal, Mr Scott said they also had to buck the trend of an Imperial system of recognition that mainly awarded medals for acts of heroism rather than general tours of duty or non-warlike service.

“Having been under the Imperial system for so long, what becomes entrenched – and I’m not being critical of the defence department and senior leadership – but they just say they haven’t done it before, and that’s that,” he said.

“And we weren’t a country in the way of people having a lot of medals on their left breast.”