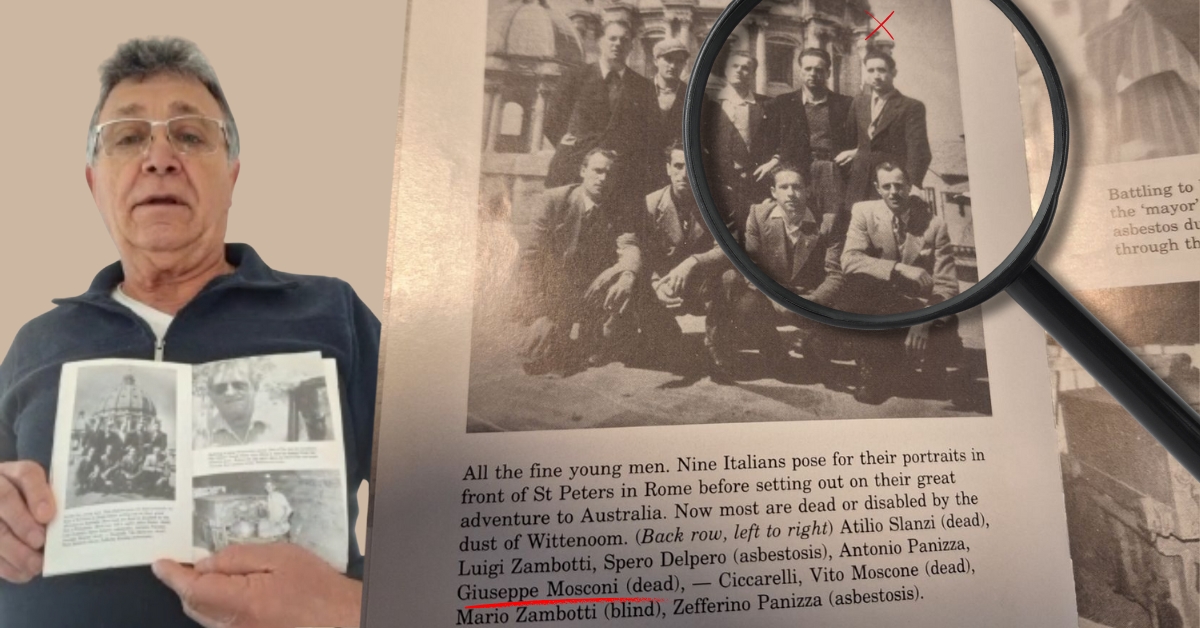

Erino Mosconi, 73, points to his 20-year-old self in his National Service photo.

Erino missed his National Service call up because his mum hid his letter. But soon enough the duty officers came knocking, and Erino’s world fell apart. To this very day, he’s never forgiven them for what they did.

Erino Mosconi had no idea he was selected in the National Service ballot of July 1972.

He missed the announcement, and his mum, Maria, hid all the evidence when it came in the mail.

“My mother hid the paperwork when I got called up for the first intake when I turned 20,” he said.

“And because I was born in Italy, they automatically deferred you a year when you didn’t respond.”

Maria was distraught to think what conscription would mean for him. It cut her even deeper knowing that Erino was all she had left after her husband died.

But there was only so long a conscripted 20-year-old could hide from the law.

One year later, Erino’s second batch of paperwork arrived. This time, he beat his mum to the letterbox, and that was it. From that moment, the government took ownership of his life for 18 months.

“There was no backing out of it, it was just get in and do it because otherwise you’d go to jail and that was that,” he said.

“You get on with it, do what you can and just keep moving forward.”

Born in the northern Italy town of Trento, near Verona, Erino immigrated with his family to Australia when he was three months old.

Erino shows a page from the book titled Blue Murder by Ben Hills, featuring the story of his father, who died from asbestos exposure.

They settled in Wittenoom Gorge, Western Australia – a town notorious for an asbestos mine, which caused fatal health complications for 2000 mine workers and residents.

Erino’s dad, Giuseppe, worked at the mine in the “crusher”.

“He’d have 30 mil of blue asbestos all over him, and they just ate it and breathed it, so he wasn’t going to live much longer,” Erino said.

His dad then packed-up the family and moved further east to start a long-haul freight company, but the damage was already done.

Giuseppe died in 1959 aged only 42. He was one of 14 Italian immigrants from Erino’s home town who died from asbestos exposure.

“Fourteen men went there from my village and they’re super fit,” Erino said.

“All of them died from either mesothelioma and asbestosis, when your chest goes hard like a rock.

“With the shock of my father dying, and the fact my mum couldn’t speak English, she ended up losing the trucking business, and that just saw her on her way.

“Mentally, she was almost schizophrenic; she ended up going a little bit psycho.”

Erino was her primary carer until he received his second summons notice for conscription in the mail, and he was left with no option but to part ways with her.

“When I went for my medicals, I tried to tell them that I was the only carer for a mother that had bipolar and schizophrenia,” he said.

“I would have thought that was sufficient but according to them, there was no grace from National Service, you just had to do it.

“I was the only other relative to her in Australia; that’s why she was mentally disturbed.”

According to the Australian War Memorial, exemptions from National Service were provided to “Aborigines and Torres Strait Islander peoples, the medically unfit and theology students”.

There was one other exception for men who objected on the grounds of religious beliefs, but they still had to prove it would cause immense spiritual distress.

Temporary deferments were also available for university students, apprentices, married men, and if someone could prove that conscription would cause them financial hardship.

Without being able to prove any of those, Erino was sent packing to Puckapunyal for training and then to Brisbane, Queensland, for the duration of his service, leaving Maria behind at their home in the suburb of Highgate in Perth, Western Australia.

“When I was away she set fire to the mattress thinking there were people talking to her,” he said.

“She got kicked out of the flat, and she rented a room in Highgate where she was brutally beaten, and that’s all thanks to me not being there.”

Erino has never forgiven the government or the defence force for separating him from her.

“I have no respect for the army anymore, zero,” he said.

“When I got signed out, I just didn’t want to know about the experience anymore — that’s why I don’t think I’ll ever be able to bring myself to go to an Anzac march.

“It [conscription] destroyed 18 months of my life, and I wasn’t going to let it destroy the rest.”

Shouldn’t have been there in the first place

Aside from the situation with his mum, Erino believes he should never have been admitted into the army because of a crippling pre-existing leg condition.

“The only thing is I should have never been in National Service because my legs cramp up solid when I march or jog,” he said.

“It’s called compartment decompression, the muscles are too big for the bags the muscles are in, and when you force yourself to walk too fast or run, the blood doesn’t get to your muscles.

“Of course, when you dropped to the ground because your legs were like rocks, the lance corporals came up and kicked you and called you a lazy bastard.

“But my legs were like rocks.”

Erino even raised the issue during his medicals after he was balloted.

“I raised it with the doctors when I went to do my medical, and they didn’t want to know,” he said.

“They said you’re not going to get out of it with that.

“In my second medical, they got the paperwork out, asked if I’d been hit by a bus, and then I was in.

“This was pretty course stuff, they didn’t really give a s***.”

Erino’s experience differs from Australian War Memorial research that found 3563 exemptions were granted between 1964 and 1972. Here are some of the major takeaways:

-

-

- 553 were granted on religious grounds

- 1768 were approved for physical and mental disabilities

- 1242 were granted for conscientious objections proved in court.

-

But Erino said he was never informed of his rights to object, nor did army medical staff seem to care during his recruitment process.

“As far as I was concerned, they never guided you on where to do that,” he said.

Erino has a chequered past with the Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

As a Nasho who elected to remain in the army after conscription was abolished, he is entitled to free cancer treatment.

If only he knew about it when he was diagnosed with cancer 12 years ago, which left him $9,000 out of pocket for treatment.

He said he did not know about the benefit, so he missed the cut-off date, and the DVA refused to back-pay him.

Erino is one of 630 Nasho Fair Go members who claim the DVA never told them about the entitlement after their service.

In some good news, he has been given a pension for partial hearing loss caused by his tinnitus.

He also has separate claims for his leg surgery and a chipped bone in his body, which has been linked to his army training.

“I’ve got four other claims in at present, which have been going on over the last 18 months, but it took me two and a half years to get my claim for the tinnitus,” he said.

Erino's story doesn't stop here...

He’s one of two Nasho cancer survivors who accuse the government of unfairly rejecting them from free cancer treatment