Life without Lenny: A widow’s story of grief and survival after conscription

Lenny* was one of the happiest 20-year-olds before conscription ruined his life. He dreamt of becoming a dad and taking his wife and future children on holidays.

But Lenny was never the same once he returned from the army. He spiralled into depression and alcoholic addiction, which drove him to unthinkable extremes.

His wife was left to pick up the pieces and raise their kids alone without any government support.

She’s one of the many forgotten family victims of the 1964 to 1972 National Service Scheme. More than 50 years later, she’s ready to tell her story.

WARNING: This story broaches the subject of suicidality

For free and confidential 24-hour support, the Lifeline number is 13 11 14 or contact Open Arms on 1800 011 046

* For privacy reasons, everyone featured in this story has been given aliases, and all the photos used are not of the real subjects

Every day, Sally* goes out of her way to stop by the family photos hanging from her living room wall. It’s a ritual providing a moment of solace from her crippling anxiety, heart condition and the many doctor appointments consuming her day.

The photos are everything to her, and by everything, she means her son Lucas.

At 69-years-old, she doesn’t have many possessions, other than a small apartment, and she can’t drive because she’s battling seizures, but she has Lucas.

Lucas is her whole world, and no matter how tough life gets, the thought of him gets her through.

Photos of his big milestones hang on the wall.

His 18th takes pride of place, closely followed by the day he got his first car, which he saved up for himself. Sally was bursting with pride when he got the keys, knowing the work ethic she instilled in him. But nothing compared to the day he became a dad, and when she held her grandchild for the first time. That’s the most sacred memory of all hanging on her living room wall.

But it’s what she doesn’t have displayed that holds the key to a heartbreaking secret she’s kept from her family, even her son.

Hidden away in a locked box are photos of a man named Lenny. She hasn’t seen him in more than 50 years. Only on the rarest of occasions will she take them out, just long enough to picture his face and the good times together. Any longer than that, it becomes too much.

Lenny never got to meet Lucas, but they have an unbreakable bond as father and son, which was cruelly denied the chance to grow.

“He left home at night and said to me: ‘goodbye, I don’t know when I’ll see you again,'” Sally says.

Lenny was only 23-years-old. The year was 1973.

“Next thing I know is I got a knock on the door at 3am in the morning, with two lovely policemen at the door telling me that he’d been involved in a car accident,” Sally says.

“I was three-and-a-half-months pregnant with our first child when he did this, and when we got the coroner’s report, it said his death was caused by a road accident, possible suicide.”

No one but Sally saw the coroner’s report.

“I was three-and-a-half-months pregnant with our first child when he did this, and when we got the coroner’s report, it said his death was caused by a road accident, possible suicide,” she says.

All her family knows is that Lenny died in a tragic car crash.

Subsequent reports confirmed that his death was a suicide, and one other bit…

“The other part is he had alcohol in his body,” she says.

This is why Lenny’s photos are nowhere to be seen on her living room wall, not because she’s ashamed of what he did — she’s very understanding of the circumstances — but because his death is too painful to be constantly reminded of it.

When Sally feels up to it, she seeks out her little locked box. As she opens the lid, Lenny stares back at her, his face so full of life. After a minute or so, she packs away the slides until the next time she can brave another glance.

“I met him at a very young age, and he was a great, fantastic guy,” she says.

“He wanted to be a dad and a family man and look after everybody, go away on holidays.”

She reminisces on his kind-hearted and jovial nature, his respect for people, his easy-going and considerate manner, his love of “mucking around”, and the way he cared for his widow mother.

But he soon became a shadow of his former self.

Lenny’s life spiralled uncontrollably when he was conscripted under the National Service Scheme in 1969.

“He did his two years — I call it a jail sentence — so after he came home, he started doing all different things, like he started gambling, he started drinking, everything got depressed,” Sally says.

“We got married in 71, and by 73, I don’t think he could cope anymore, so he went out that night and went head on into a bridge.”

Sally has endured every emotion one could imagine: frustration, anger, resentment, disbelief, denial, shock — the whole gamut of feelings relating to grief.

But she doesn’t blame Lenny.

“Not knowing what was ahead of them was the worst, and they weren’t entitled to any help,” she says.

“There was never any help for the guys who never went over to Vietnam.

“They had to survive afterwards themselves, and loads of them couldn’t because there’ve been many suicides, many.”

Suicidality among Nashos is difficult to quantify.

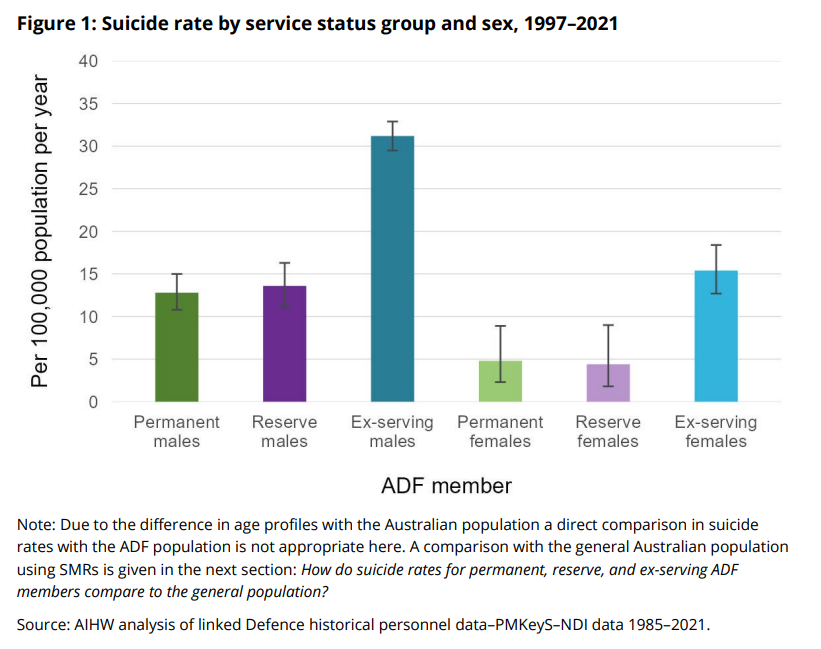

Analysis from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare found there were at least 1,677 certified suicides from the defence community – comprising past and present members – between 1997 and 2020.

On average over the last decade, 78 suicides were recorded annually. This equates to three every fortnight, according to the Royal Commission into Defence and Veteran Suicide.

The commission’s chair Nick Kaldas says this was “more than 20-times the number killed in active duty over the same period”.

Ex-serving members are over-represented in the figures. Since 1997, the annual number of suicides among this group has progressively increased from the high 40s to the high 60s and 70s.

Crucially, the Royal Commission found that the DVA was failing past and present ADF personnel and their families, leaving loved ones like Sally to pick up the pieces alone.

She claims she couldn’t get a war-widow pension because social security told her Lenny didn’t fight overseas in a war zone.

She says they then denied her an unmarried mothers pension because she was still pregnant and wasn’t yet classified as a mother.

“And I said, ‘oh, okay, well what am I?’” she recalls from her conversation with social security.

“So, I was a nothing.”

Her treatment speaks to a major problem with Nashos being rejected from entitlements because they didn’t serve in recognised war zones, which influences the support available to family members.

The war-like eligibility test neglects the many other ways that domestic deployments affected their lives.

The job losses, stunted career prospects, shattered earning potential, and the huge psychological detriment created major setbacks that are easily overlooked.

They also served during a time when veteran welfare was a fledgling concept, nowhere near the level it is today.

Thousands of Nashos and their families feel aggrieved that more wasn’t done to support them afterwards.

“There are probably other women out there who were in the same boat as I was, we had to do it alone, we were nothing because our husbands didn’t serve overseas,” Sally says.

“But there’s people out there who are 10 times worse than I am. I class myself as lucky I got through it, with a few problems myself, I got through it.

“I’ve got hardened to the fact that I don’t want what happened to me after that to happen to any other lady of man in the situation I was left in by the government and all the rules and regulations.”

As hard as it was, the ordeal gave her a unique ability to help others who were stricken by grief and trauma.

As hard as it was, the ordeal gave her a unique ability to help others who were stricken by grief and trauma.

Helping them became an important part of her own healing process.

“I started working for a company that trained me to go into houses and help people back then that had some sort of depression problem, so I could sit down, talk to them, and be with them,” she says.

“Then I left that and went into doing the same thing with people that were having cancer and chemo.

“I’d go in, sit with their kids, and take their kids to school and give mum a break, and I just started trying to help people.”

Today, Sally still catches herself wondering what could have been if Lenny was still here.

“I blame myself in some ways — was there something else I could have done to help him?” she says.

“I just don’t know the answers to those questions, I’ll never know the answers.”

The ordeal has seriously affected her health.

“I am not a well person, I’ve had a pretty torrid life with everything,” she says.

“I’ve just had a seizure, and through trying to protect and give what I can to people, I’ve had breakdowns.”

While Lenny’s secret can be a tough cross to bear, she knows it’s for the best.

“I didn’t want to hurt anybody, like my brother in law and sister in law had a couple of young kids, and it was very traumatic for them anyway, and I kept most of it to myself from when I noticed a change in him,” she says.

Sally won’t even tell her son — ever.

“No, only because my son didn’t know his dad, and he’s seen photos of him, and I don’t want him to be upset,” she says.

“But my son is a funny guy, he hates talking about the past, and his father’s in the past.”

Sally says the hardest part about raising a child as a widow was confronting Lucas’ milestones.

Her yearning for Lenny at those times was profound. Lucas’ 23rd birthday was particularly significant in the grieving process.

“I lived on my nerves until my son — our son — reached his father’s age,” she says.

“It was like a load of my mind when he got there, and I thought, well, you’re going to be right now, you’re going to be fine, you’re not going to die.

“I was frightened, but once he got over that hurdle, I was happy, you know, well there you go, your father would be proud.”

Hear Sally’s full story on The Men Australia Forgot podcast Ep6 – I was a nothing