It’s a sad state of affairs when veterans who nearly died in combat are rejected from entitlements because they don’t meet the definition of “war-like service”.

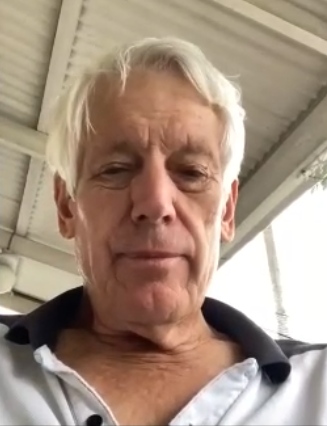

For 79-year-old Nasho Graham Parlour, an arbitrary date derailed his genuine claim to a Gold Card – Australia’s most generous and comprehensive veteran benefit.

Nasho Graham Parlour is almost 80, yet he hasn’t yet been recognised for the Gold Card despite almost dying in combat.

He was almost killed during a firefight against communist terrorists while serving in Malaya in 1967/68. But he’s been rendered ineligible because he arrived 6 months after the cut-off date for operational service.

No amount of rational discussion with the DVA will change it. The rules, as Defence and Veterans Legal Service entitlements officer Nicholas Warren said, are iron-clad and notoriously technical.

Even if Mr Parlour arrived one day after the cut-off of 14 September 1966, he’d still be refused.

As Mr Warren puts it: “If you are 10 miles out of that location or two days late, you simply don’t get that classification of service.”

It’s a brutal way to treat our veterans who served on the front line.

His experience is symptomatic of a broader problem affecting Nashos.

So often it seems government officials are so obsessed with being technically correct, according to the law, that they are incapable of making logical exceptions for veterans in desperate need.

I was talking about this recently to former Howard government minister, the Hon. Gary Hardgrave, who was influential in pushing the proposal for the National Servicemen’s Medal through parliament in the 1990s.

He summed it up beautifully when he said the government spends tens of millions of dollars building bureaucracies designed to stop veterans from getting the help they need.

Mr Hardgrave said politicians waste too much time and money poring over arbitrary details during reviews and inquiries to assess eligibility, when it’s cheaper under certain circumstances to just give them the benefits they’re asking for.

There’s a compelling argument to apply this logic to the Nashos of 1965-1972, given everything they went through and their limited years left.

The DVA claims process is already in crisis. By July 2026 when the landmark harmonisation reform comes into effect – delivering improved Gold Card eligibility for some Nashos and more lenient claims assessments – the oldest Nasho from the 65-72 cohort will be 82. They might still have to wait hundreds of days to see an outcome given current turnaround is 370 days, which is down from 438 days this time last year. Realistically, they will not live to enjoy the quality of life afforded by any potential entitlement awarded under the new act, and they risk passing away before seeing an outcome.

There are also serious questions surrounding the productivity of existing inquiries. While they have revealed some extremely important findings, what’s the point if very little comes from them?

The Royal Commission into Defence and Veteran Suicide found the Australian Government formally responded to fewer than half of the previous 57 veteran-related inquiries or reports, assessed throughout the commission.

Since 2000, the government has completed 50 reports relating to suicide in the veteran community, which made more than 750 recommendations. But in a damning assessment, the Royal Commission said it was “dismayed to come to understand the limited ways that Australian Governments have responded to these previous inquiries and reports.”

Now let’s look at costs. Approximately $23.6 million funded the inquiry into recognition for members of Rifle Company Butterworth. More than $7 million was spent on the Afghanistan inquiry, resulting in the Brereton Report. Approximately $1.9 million was spent on the 2011 Review of the Military Compensation Arrangements.

Three inquiries. $32.5 million. And to think there could be at least another 28 that haven’t been responded to. It’s alarming how much may have been spent on white papers without anything tangible to show for it.

Money like that could have funded more than 1,200 Gold Cards for deserving Nashos, like Mr Parlour, based on the DVA’s estimate that it would cost just over $26,100 per card.

While Nasho Fair Go is no longer pursuing the Gold Card for all 65-72 nashos, it demonstrates what money can buy.

In their case, they’re now after private medical and dental cover. The government said it’s considering the proposal, but at what rate? As Greens senator and veterans spokesperson David Shoebridge said: “the bloody thing is glacial.”

Any concerns of cost should be tempered with the understanding that it would likely be a 10-year outlay, not a 40- or 50-year commitment like it is for other younger veterans.

The government has a chance to right the wrongs and give the 65-72 Nashos a genuine form of reparation, unlike the stock-standard White Card they’ve been told to accept as an olive branch, which is available to anybody who does one day of continuous full time service in the army.

It doesn’t have to be as complicated as it’s being made out to be either. Senator Shoebridge said a lot can happen quickly with ministerial intervention. The Defence Honours & Awards Appeals Tribunal said as much in the Rifle Company Butterworth inquiry handed down last year. It found that only two ministerial actions would be required to award a group of veterans the Australian Active Service Medal. First, a defence minister would have to recommend it to the Governor-General, and second, the Defence Minister would have to re-classify their service as “war-like”.

Continuing to drag aggrieved Nashos through administrative procedures to determine their worthiness for higher levels of benefits will only alienate them further.

They deserve better after being forced to work in the army under the threat of imprisonment.

It requires our politicians to look beyond the scope of war-like eligibility and consider their case of service as a human rights issue, which should, in itself, justify better entitlements than what they have.